Introduction

The Kirthar Mountain Range in Sindh, Pakistan, is among the most remarkable ancient landscapes of South Asia. It preserves traces of prehistoric human activity, early settlements, and enigmatic petroglyphs (Sindhi word Chitt). These carvings, found on rocks and in caves, hold immense archaeological value and connect Sindh with wider global traditions of prehistoric rock art.https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kirthar_Mountains

The Kachho Region and its Landscape

The Kachho region, lying in the foothills of the Kirthar mountains, is a natural ecological zone. Several streams flow here, the most significant being the Naen Gaj, which irrigates the fertile lands of Kachho and eventually flows into Manchar Lake. This environment provided ideal conditions for early human settlements.

Ancient Beliefs and Cultural Traces

Within Kachho, remnants of ancient belief systems still survive, though many have been reshaped under Islamic culture. Some traditions trace back to pre-civilizational or animistic practices. Sacred stones, tree veneration, and symbolic rituals reflect continuity between ancient and later traditions.

At the shrine of Ghaji Shah Khoso, symbolic graves and ritual practices demonstrate how deeply rooted these traditions are. The unexplored Kaloi mound (Kaloi Jo Daro) further points to the region’s archaeological richness, waiting for systematic study.

Prehistoric Settlement in Kirthar Mountains

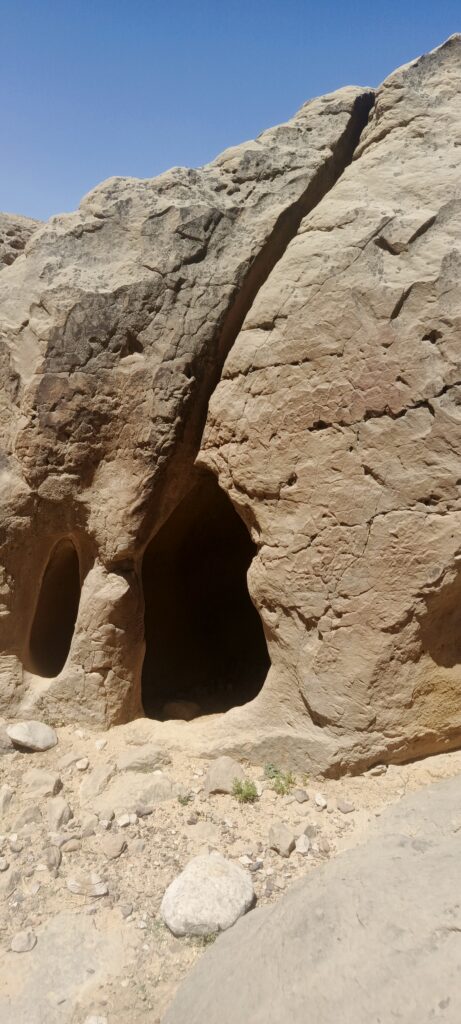

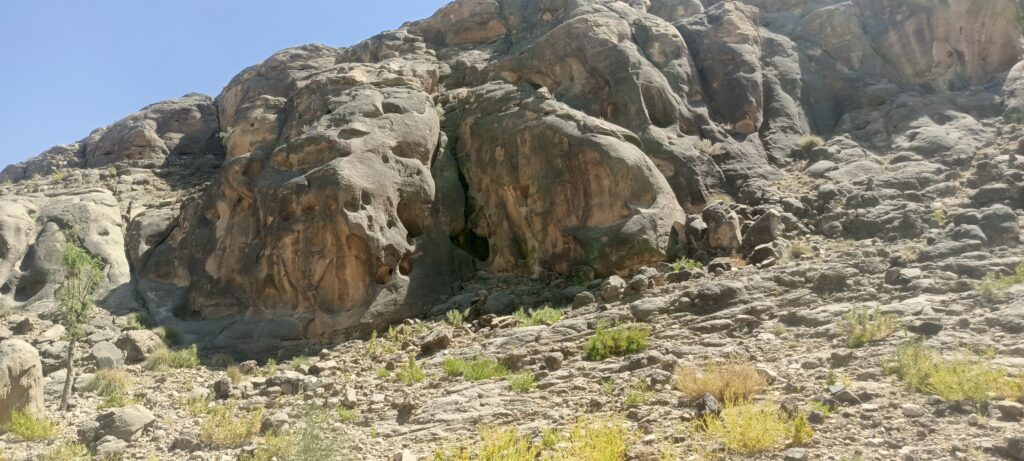

The prehistoric caves of Kirthar confirm that humans inhabited the region since ancient times — from the nomadic era to more organized civilizations. During the medieval period, the mountains also acted as natural routes for Iranian and Arab invasions, showing their role as both a habitat and a corridor of migration and movement.

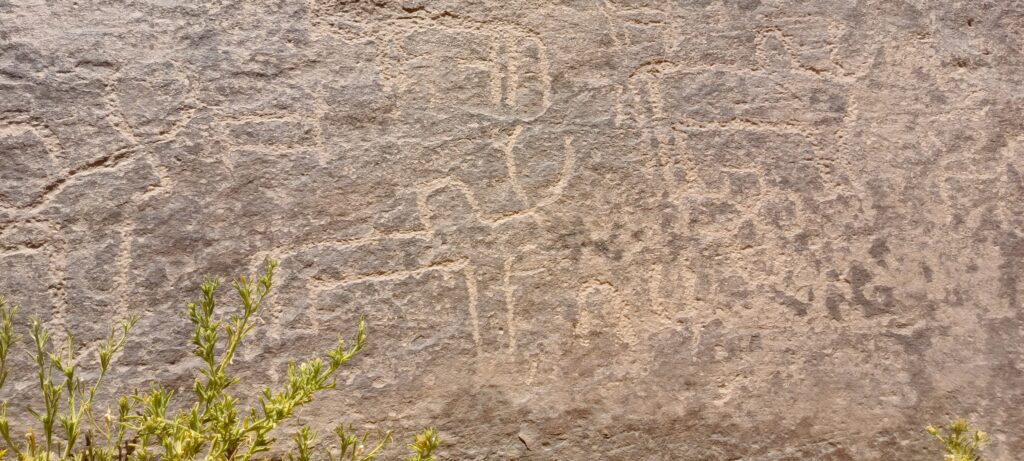

Discovery of Petroglyphs at Pachal

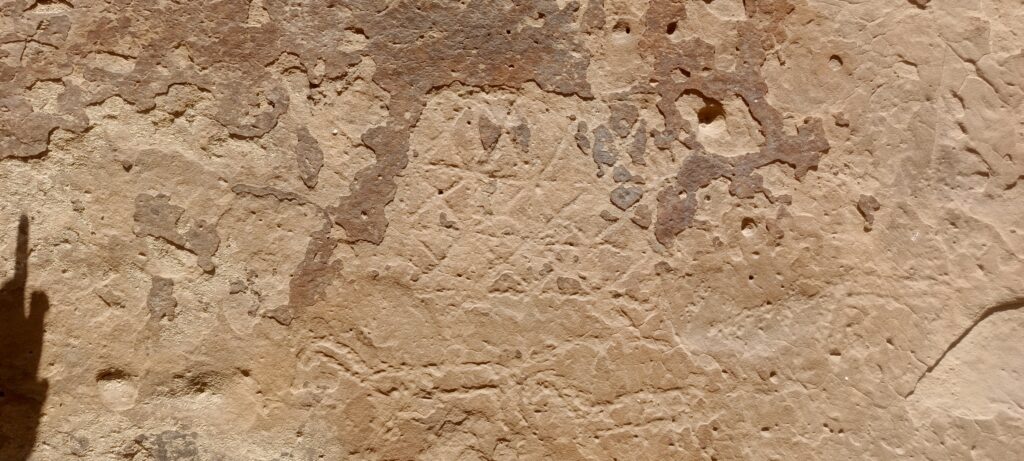

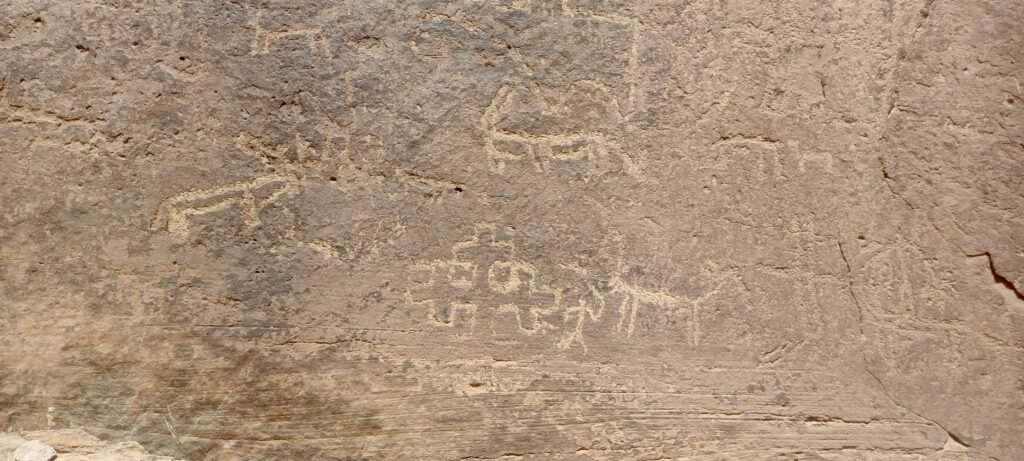

On ascending from Tando Rahim and Ghaji Shah shrines towards Gorakh Hill, a peak called Pachal reveals numerous petroglyphs. These carvings include depictions of humans, bulls, and animals.

In front of these petroglyphs, there are also two caves. It is possible that the people who created these carvings may have temporarily or permanently lived in those caves.

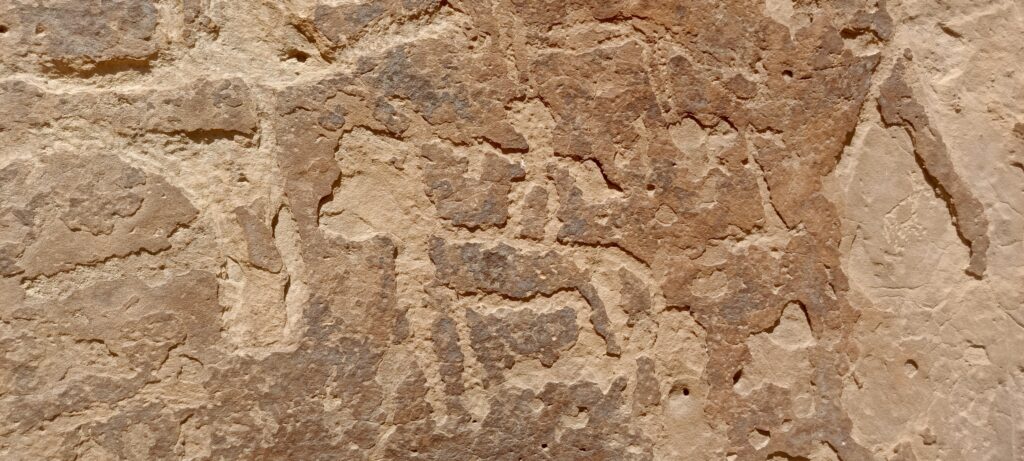

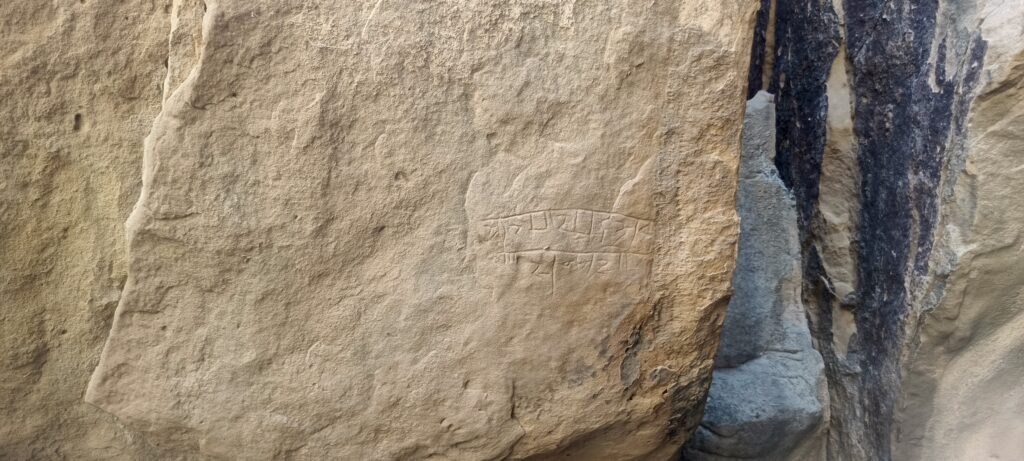

Nearby caves also contain inscriptions in Brahmi and Devanagari scripts, indicating cultural layers from prehistoric to medieval times.

These petroglyphs are not as large as the famous Dabous Giraffe Petroglyphs of Africa, yet they are equally significant. Notably, carvings of bulls and horse riders strongly resemble those of the Indus Valley Civilization (Mohenjo-daro).https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo-daro

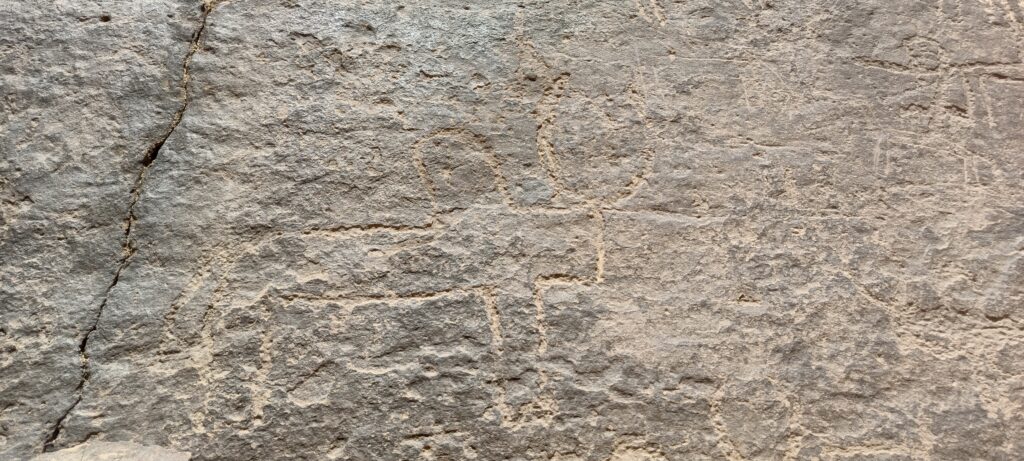

Global Connections: A Spiral Mystery

Among these carvings, a spiral petroglyph is especially intriguing. Its design closely resembles the spiral petroglyphs of Sinaloa, Mexico, suggesting a symbolic connection with global prehistoric traditions. The similarity also highlights the universality of spiral motifs, often associated with cycles of life, energy, and the cosmos.

Antiquity and Interpretations

The exact age of these carvings is not yet known. However, inscriptions in Devanagari script suggest that some belong to the medieval period. One inscription is believed to reference the Naga (serpent deity), symbolizing the endurance of ancient Indic beliefs.

There is also a strong possibility that these carvings were made by communities from the Indus plains, who later abandoned their mountainous lifestyle and contributed to the rise of the Indus Valley Civilization at Mohenjo-daro.

Preservation and UNESCO Recognition

There is an urgent need to protect this site as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Like other global rock art traditions, these petroglyphs deserve detailed archaeological study. Comparative analysis with Mohenjo-daro motifs, as well as similar petroglyphs in Africa, Mexico, and beyond, may reveal a shared prehistoric symbolism and help establish their true antiquity.

Conclusion

The petroglyphs of the Kirthar Mountains are not only a cultural treasure of Sindh but also part of the global heritage of humanity. Their study can shed light on the prehistoric imagination, symbolic traditions, and the transition from nomadic to urban life. Preserving these carvings is essential for both regional identity and world archaeology.

Write: GM Leghari